Reflections about the phenomenon of community art

Irene Calvis – El Liceu

19.01.2021

Main Hall of the Gran Teatre del Liceu. Photo by @PACO AMATE

To understand why an institution like the Gran Teatre del Liceu, with a history going back over 170 years, decided to launch a project line of community art; we must review its past and its evolution over the years. For both Barcelona and Catalonia, the Liceu is a key cultural facility with a clear awareness of its own history, which seeks to achieve artistic excellence and disseminate operatic culture while keeping closely tuned in to developments on the international opera scene.

The Liceu was originally set up as a private company with shareholders. During its early years, it competed with the Teatre de la Santa Creu for theatrical dominance in the city and provided a venue for performances by a music and drama school: the ‘Liceo Filarmónico Dramático Barcelonés.’ The new theatre, an elegant spacious building, in keeping with its artistic ambitions, was built in 1847 on the site of a former convent. The plays and operas performed there became the highlights of city life and the Liceu itself became a meeting place for the Catalan elite. In spite of its middle-class origins, it looked out onto the Rambla, a thoroughfare that marks the border of the Raval, a district where demands for freedom of expression have often arisen in the city’s history.

As time went by, operas by Verdi and Wagner were billed more often than others, great singers triumphed there, and the Liceu emerged as Catalonia’s leading opera house. However, despite offering one of the longest opera seasons in Europe, its system of funding eventually became obsolete in comparison with other opera houses. In 1980, after democratic elections had led to the formation of Catalonia’s first autonomous government in recent times, a Consortium including the different levels of government was set up to manage the Liceu. An unstoppable trend towards greater openness to the city and the whole country was underway.

As befitted an opera house under public management, the Liceu’s new project was aimed at society as a whole. Its mission was to create aesthetically ambitious art, make it available to the largest possible number of citizens, and afford the country’s own musicians and creators ever greater opportunities. In the 1980s and 1990s, key programmes were launched to boost the dissemination of opera, notably by the Liceu’s educational service. Following a new budget; flexible subscriptions were put on sale, DVD recordings of Liceu productions became widely available, the design of the main auditorium was improved to make it one of the most accessible in Europe, regular tours of areas of the opera house open to the public were offered, an alternative programme of small-format shows in the Foyer room was created, the association Amics del Liceu was founded to support the opera house and give prominence to its programme, and the project ‘Liceu al Territori’ made it easier for audiences from outside the Barcelona metropolitan area to reach the opera house. After the 1999 fire, which destroyed part of the building, all of this was encapsulated in a new slogan: “El Liceu de tots” (A Liceu for Everyone).

Performance of the opera Oh! L’amor included in the project Òpera a secundària (Opera in high school project), during the Season 2014-2015

These policies based on openness and proximity led in turn, as Liceu intended, to a social programme designed to facilitate social integration by guaranteeing easier access to culture for those in vulnerable situations. Equity, high quality, commitment and solidarity are the values upon which the Liceu is structuring its programme around a whole range of services, activities and benefits. Other forms of accessibility have come to attention: the live audio-description service for people with visual-impairments which has been available at all dramatized shows since 2005, and the specially adapted plot synopses in an Easy-to-Read format for people with functional diversity, migrants and those with reading difficulties. Various discounts are offered on the basis of disability, social vulnerability or for family reasons. Under the programme ‘Òpera a l’abast’, special informal talks, complete with music, are organized on premises belonging to social organizations, after which the participants attend a rehearsal at the Liceu. Another programme, ‘Apropa Cultura‘, provides for 4,000 tickets for seats in good locations to be made available every season to the users of social organizations at the price of 3€ each.

So is there more we can do? Let’s review our existing projects. So far the Liceu has opened up to new audiences, mainly by providing them with passive enjoyment. We offer seats and accessibility, certainly, and other benefits and activities as well. But everything is based on listening; the participants are mere spectators. There have been a few exceptions. In 1999, the Liceu joined up with Barcelona City Hall in staging a series of performances of the opera Brundibár, by the Czech composer Hans Krása, in which pupils from Barcelona schools with no musical training sang the choral parts. Later it created a whole new programme based on the same philosophy, ‘Òpera a Secundària’, but focussing on new operas. And then there was Jonathan Dove’s magnificent El Monstre al laberint (The Monster in the Maze) which called for the participation of large numbers of students from schools throughout Catalonia. It was to have been performed last season but had to be cancelled on account of the pandemic.

Video of The Monster in the Maze (El Monstre al laberint)

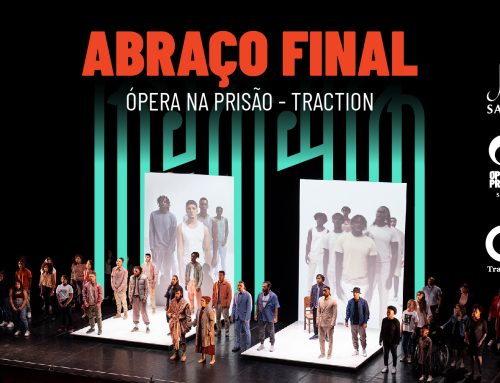

So our new line of projects for community artistic processes is a step forward: it seeks to give all kinds of people a voice at the Liceu, a cultural facility that belongs to all. There will be a phase of active listening before the creative process starts to offer individuals, each with their own specificity, the right to play an active role in the act of creation. But can opera be created out of social inclusivity and cultural diversity? Let’s try, let’s put our hands to the wheel and set down the objectives in black and white: to place opera within reach of a diverse population, to bring people’s talents to light, to encourage cultural diversity and open-mindedness, and to offer the opera house itself a highly challenging experience which will forge closer bonds with its immediate surroundings.

Will we be up to the task? Can we adjust our gaze even more closely to people we don’t know, who are different from us? For any cultural institution, joining with people from a range of social and cultural backgrounds to carry out a creative project is inevitably a challenge and an act of humility. It means leaving our comfort zone and opting for new forms of cooperation outside the professional operatic world. But we will be working in a district with a strong tradition of voluntary associations, a district rife with talent, contrast and varied potential; with a rebellious, fighting spirit and an instinct for survival; a district shaped, in both human and economic terms, by the many migrants who have settled there because it is one of Barcelona’s points of entry. We must highlight its qualities while avoiding paternalism from those who believe themselves superior; we must foster appreciation of its people who are different from ourselves, never concealing the stark reality of many of its features but stressing inclusivity and complementarity instead. The Raval is the most deeply stigmatized of all Barcelona’s districts. Despite the fact that many city residents are not familiar with their multiple reality, there is a growing desire to discover it. Art, culture and music must act as vectors of optimism, transformation, emotion and permeability. For our venerable opera house, this project will be a major step forward but if it is to be more than a token of good will, if it is to forge real bonds with the community and become a genuine, effective project for change, it must be approached in the right way. How? By exploring and diagnosing, by defining the objectives, planning the phases and the pace, selecting methodologies, and then observing and evaluating the results. And we must enlist help, cooperation, advice and support from those experienced in stimulating artistic endeavours at grassroots level.

These are difficult times for undertaking community projects because of the current dystopian world situation, which raises obstacles to human contact and synergy, questions our superior status in the world and invites us to redefine our relationship with the environment and the species that inhabit it. By acknowledging our vulnerability, weaknesses and limitations and learning from our mistakes, we can act as agents of opportunity and launch a major transformation. This project aspires to be a small, indeed a minute example of how an opera house in a medium-sized city such as Barcelona, in the tired old European continent on the marvellous planet Earth, can strive to use artistic creation to bring about change and mutual enrichment. We are not alone, however. We can rely on assistance from specialists in music, opera and new technologies, experts in community artistic processes, academic researchers and all the courageous people who support the exciting and motivating project called TRACTION. In the coming two years we will experiment and learn together, pooling processes, technology and evaluations… in short, everything that facilitates operatic creation with a view to changing society for the benefit of its most vulnerable members.