O Jakson e o Fábio

Jackson, RAP Don Giovanni ‘Freedom’: Prisão de Leiria, Portugal © SAMP

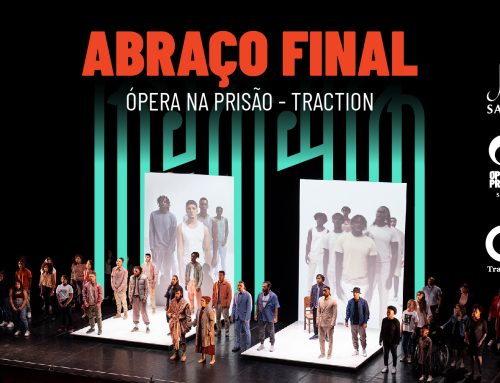

Os jovens reclusos de Leiria conhecem bem o logro e a morte, na vida, mas também nos palcos. A tragédia humana é o seu dia-a-dia, e a Ópera é uma palavra que lhes é familiar. Em 2015 já lhes morreu a seus braços um Comendador, morto pelo chefe dos guardas prisionais, e interpretado pelo também director da Prisão. Em 2018 vestiram-se de Dons Alfonsos e enganaram, mais uma vez com a partitura de Mozart, dois jovens casais que Lorenzo da Ponte lhes havia apresentado. Mas em 2020 alguém invadiu a prisão para lhes dizer que Mozart e Lorenzo da Ponte há muito haviam morrido, muitos já não se lembravam, e que se chamava TRACTION o novo projecto Ópera na Prisão.

TRACTION?!!! Traction não é um nome italiano. Como pode ser uma ópera?! E quem morre nesta história? As nossas mães podem entrar cá dentro para cantar connosco? E vai haver computadores e telemóveis na orquestra?!!! Foram muitas as primeiras perguntas, carregadas de desejo pelas memórias que ouviram contar do Don Giovanni e do Così Fan Tutte das edições anteriores. Foi assim, no início de 2020, que o Traction entrou no Estabelecimento Prisional de Leiria, a prisão portuguesa que recebe jovens entre os 16 e os 25 anos de idade.

Primeiro falaram entre si os que estão presos cá fora. Presos às agendas de trabalho e à legislação da justiça nacional. Presos às rotinas das orquestras e à ditadura dos criadores. Presos aos horários escolares e às escalas de serviço dos guardas prisionais. Quando todos estes presos se entenderam entre si, estávamos preparados para entrar na Prisão e começar o projecto. Mas ninguém nos havia avisado que políticos e maestros, psicólogos e guardas, pianistas e poetas, directores e juízes, iriamos todos ficar presos 3 meses na Cela 19. Foi a pena que a COVID a todos nos aplicou inesperada, implacável e criativamente.

Contra ventos e marés, entre tempestades perigosas, abriram-se as grades e nasceu um grupo de 40 rapazes, 3 compositores, 1 escritor, uma encenadora, uma psicóloga, e alguns loucos mais. Portugueses, brasileiros, africanos, latino-americanos, todos desejosos de cantar e abraçar. Nem uma nem outra coisa se podia fazer. Oficialmente. Porque uma prisão é o lugar mais livre da cidade. Cumpriram-se todas as regras e cumpriu-se um desejo maior. A ópera Traction seria feita por todos e não por Mozart com o Lorenzo da Ponte. Vamos fazer uma ópera pelas nossas mãos e nela contar de nós e do que nos interessa e apaixona.

Ensaio Don Giovanni: Prisão de Leiria, Portugal © SAMP

Fotografia por Joaquim Dâmaso – Ensaio Così fan tutte: Prisão de Leiria, Portugal © SAMP

Os compositores falaram de si e das suas obras, todas muito eruditas e clássicas. Quase não pareciam obras deles, porque o Nuno, o Francisco e o Pedro, são pessoas simples como todos nós. O Paulo Kellerman, que escreve histórias e poemas, ouvia deliciado as descrições e os desabafos que os rapazes faziam a todo o instante. Ouvimos histórias dos reclusos mas também dos guardas e dos técnicos prisionais. Também cantámos, sempre com máscara e muito afastados, porque as prisões são jardins amplos e arejados. Identificamos baixos e tenores, vozes sábias e assustadas, vozes roucas e revoltadas, e cantámos para afastar mágoas e aproximar corações.

Chegou o verão quente e com ele mais COVID. Tivémos de abandonar o ar livre e recolher-nos aos pavilhões das celas. Foi assim na cozinha, o espaço possível, que as primeiras 10 histórias destiladas pelo Paulo Kellerman começaram a ser debatidas. A cozinha pode não ser a melhor sala para um recital de canto, mas é sempre um espaço privilegiado para a co-criação. Escolheram-se palavras para uma história como se escolhem ingredientes para uma sopa. Falou-se de Kafka e dos números que escondem os nomes. De Cervantes e dos Quixotes que sonham como as mães dos rapazes. Dos labirintos e cegueiras de vida e do Nobel José Saramago. Quando se falou das escolhas e dos caminhos chegou-se a Dostoievski. A culpa levou-nos todos a Paul Auster, e a ditadura e liberdade conduziu-nos até Italo Calvino.

Mas um dia a mãe do Fábio voltou à prisão. Não para visitar o seu filho, mas para levar a sua roupa e os poucos haveres que ali tinha deixado. O Fábio tinha cantado o Così fan Tutte, e nele ganhou paixão pela dança contemporânea. Era um apaixonado pela vida e todos éramos apaixonados por ele. Morreu trucidado por um comboio e trucidou a vida da mãe que perdeu o filho único. Com ele todos fomos trucidados naquela linha de Comboio em Caxias. Fez-se silêncio quando se disse que a mãe do Fábio havia chegado à prisão. Ninguém conseguia mais pensar em palavras e em histórias para uma ópera. Sem orquestra e sem libreto, sem encenador e sem maestro, o Fábio e os olhos grandes e sofridos de sua mãe superavam a mais pungente das melodias de Puccini.

Fotografia por Joaquim Dâmaso – Fábio e sua mãe: Prisão de Leiria, Portugal © SAMP

Passou uma semana e mais uma semana. Agora os guardas, em especial a Chefe Fátima, manifestavam vontade que a ópera Traction falasse da história da sua prisão. Esta prisão de Leiria que é ainda uma quinta, foi uma cerâmica e uma serração, oficina de automóveis e vacaria, encadernação e tipografia. Sempre com guardas prisionais tipógrafos e sapateiros, mecânicos e carpinteiros, tanoeiros e vinhateiros. É mais fácil educar com um pincel e uma serra do que com uma arma. Mas hoje a prisão é pouco quinta e já sobram poucos destes guardas especialistas. Carpinteiro é ainda o guarda Guerreiro que nos faz os cenários das óperas e constrói o palco que permite receber uma orquestra clássica dentro da prisão. Sim, até os reclusos gostavam de contar esta história de outros tempos, mas têm dúvidas se não será pouco para uma ópera. Eles viram e ouviram Mozart, emocionaram-se com Farinelli, desejam ir ao Gran Liceu a Barcelona, e as óperas contam sempre grandes histórias de heróis e amantes. Como podemos nós ser tema de uma ópera? Nos últimos dois meses, todos os dias a equipa criativa SAMP sai da prisão com os cadernos e as mentes cheias de histórias. Nem o Verismo mais puro consegue fazer justiça à maioria das histórias destes rapazes. Quão pobres são os libretos ao lado do que nos contam os reclusos com os olhos e as palavras. Mas vivemos em mundos paralelos, e estes primeiros tempos de co-criação começam por ser antes de mais tempos de encontro. Ouviu-se um tiro.

O Jackson foi abatido a tiro pelas costas. O Jackson não tinha família para o acolher depois de cumprir a sua pesada pena. O Jackson cantou o primeiro Don Giovanni do Ópera na prisão em 2014, e compôs um RAP que cantou no final da récita acompanhado pela orquestra e empunhando uma bandeira com a palavra liberdade. Quando saiu em Liberdade foi ao Teatro Nacional de São Carlos em Lisboa para pedir emprego. Invocou para sua defesa que já tinha cantado o Don Giovanni e sabia de cor toda a partitura no seu italiano crioulo.

É neste emaranhado de ficção criativa e realidade que estamos todos neste momento. Só sabemos que até Dezembro 3 histórias têm de estar prontas para entregar aos compositores. Esperamos todos que não volte a morrer mais nenhum dos rapazes na vida real porque já temos ópera suficiente para o Traction.

Paulo Lameiro, com David, Sofia, Raquel, Sandra, Anabela, Carla, Nuno, Francisco, Pedro, Paulo Kellerman e muitos outros

Jakson, RAP Don Giovanni ‘Freedom’: Leiria Prison, Portugal © SAMP

These young inmates in Leiria are no strangers to deception and death. The themes have followed them throughout their lives, but also on-stage. While human tragedy is a part of their day-to-day existence, the word “Opera” has made it firmly into their vocabulary. In 2015, a Commendattore died in their arms, killed by a Senior prison Officer and played by the Prison Governor. In 2018, they dressed as Dons Alfonsos and deceived two young couples introduced to them by Lorenzo da Ponte in a scene once again scored by Mozart. In 2020, however, someone broke into the prison to tell them that Mozart and Lorenzo da Ponte had long since died, that many didn’t even remember them at all, and that the new “Ópera na Prisão” (Opera in Prison) project was called TRACTION.

TRACTION?!!! Traction isn’t an Italian name. How could it be an opera?! Who dies in the story? Can our mothers come inside to sing with us? And will there be computers and mobile phones in the orchestra?!!! The first round of questions rained down after the announcement, from a group filled with desire for memories forged by previous performances of Don Giovanni and Così Fan Tutte. It was thus, in early 2020, that Traction was brought into the Leiria Prison for young offenders, a Portuguese prison facility for young people aged between 16 and 25.

The start of the path had been forged by a conversation held between those incarcerated on the outside. Imprisoned by work schedules and penal justice legislation. Stuck behind the bars of deep-rooted orchestra routines and the under the thumb of a dictatorship of creators. Jailed by school times and prison officer shifts. And it was only when all these prisoners began to see eye-to-eye that we were finally ready to go into the Prison and start the project. But nobody had warned us that all of us – politicians and conductors, psychologists and guards, pianists and poets, directors and judges – would be locked in cell 19 for all of 3 months. A sentence imposed by COVID, bestowed upon all of us unexpectedly, relentlessly and creatively.

Against wind and tide, amidst dangerous storms, the bars fell away, and a group of 40 young men, 3 composers, 1 writer, a director, a psychologist, and some more risk-takers emerged. A mixed bag of Portuguese, Brazilian, African, English and Latin Americans, all eager to sing and embrace each other. They could do neither. Not officially, anyway. Because there is more freedom in a prison than anywhere else in a city. The rules were followed, and an even greater desire fulfilled in the shape of an opera – Traction – which would be conceived by all of us, not Mozart or Lorenzo da Ponte. We would craft an opera ourselves, and use it to talk about the people involved, what interests and captivates these individuals.

Don Giovanni rehearsal: Leiria Prison, Portugal © SAMP

Photograph by Joaquim Dâmaso – Così fan tutte recital: Leiria Prison, Portugal © SAMP

The composers talked about themselves and their works, which were all very scholarly and classical. They were almost unrecognisable as their own, in fact, because Nuno, Francisco and Pedro are ordinary people, just like the rest of us. Paulo Kellerman, who writes stories and poems, listened to the youngsters’ constant narrations and outbursts with delight. The inmates held the floor, but so did guards and prison technicians. We also sang, ensuring our faces were safely covered with face masks and that we were keeping our distance from each other, made easier by prisons being essentially large, airy gardens. We picked out the bass and tenor voices, those that sounded wise and those frightened, hoarse and angry, and we sang to heal our wounds and bring our hearts closer to one another.

The heat of summer brought with it more of the virus. We had to retreat from the blazing sun by reverting to the cell blocks. That was how the kitchen, the only room big enough, became the location where the first 10 stories refined by Paulo Kellerman were debated. And while a kitchen may not be the best room for a voice recital, it has always been a room that inspires co-operative creativity. Words were chosen to fuel a story just as ingredients are selected for a soup. The conversation featured Kafka and names hidden within numbers. Cervantes was brought in, as were Quixote-types, dreamers like the boy’s own mothers. The labyrinths and blindness faced in life were discussed along with José Saramago’s Nobel Prize. When the conversation turned to choices and paths, Dostoevsky held out a helping hand. Guilt led us towards the words of Paul Auster, and dictatorship and freedom to Italo Calvino.

But one-day Fábio’s mother came back to the prison one last time. Not to visit her son, but to pick up his clothes and the few possessions he’d left behind. Fábio had sung Così fan Tutte, and through it gained a passion for contemporary dance. He was passionate about life, and we had all fallen head over heels for him. His life was torn from him by a train, ripping his mother’s life to shreds as she lost her only child. And our insides had been shredded just as savagely as his, on the train line in Caxias. Deafening silence descended upon us when the announcement was made that Fábio’s mother had arrived at the prison. Any words or stories for an opera that had been floating between us previously had now disappeared. They didn’t have an orchestra or a libretto, a director or conductor, but Fábio and his mother’s wide eyes filled with suffering were more heart-breaking than the most poignant of Puccini’s melodies.

Photograph by Joaquim Dâmaso – Fábio and his mother: Leiria Prison, Portugal © SAMP

A week went by, followed by yet another week. The guards, Chief Fatima in particular, began talking about the Traction opera telling the story of the prison. This prison in Leiria, which is still a farm of sorts. A building that has been a ceramics factory and sawmill, a garage and cattle farm, used for bookbinding and typography. The correctional officers have always been typographers and shoemakers, mechanics and carpenters, coopers and winemakers. It is, after all, easier to teach with a brush and saw than with a gun. But nowadays, the prison’s farming operations have almost reached the point of extinction, and the specialist guards of yesteryear are few and far between. Our Carpenter is the guard Guerreiro, who makes our opera sets and builds a stage to host a classical orchestra inside the prison. Yes, even the prisoners yearn to share the story of this prison’s past, though they worry about not having enough material for an entire opera. They’ve watched and listened to Mozart, been touched by Farinelli and felt the draw of the Gran Teatre del Liceu in Barcelona. And operas always tell great tales of heroes and lovers. How could they possibly be the subject of an opera? Every day of the last two months, the SAMP creative team has walked out of the prison with their notebooks and minds full of stories. Not even the purest Verismo could do most of these boys’ stories justice. How lacking the librettos now seemed when compared to what the prisoners told us with their eyes and words. But we live in parallel worlds, and these first creative meetings, opportunities for co-creation, were, before all else, an opportunity for us to come together. A gunshot rang out.

Jakson was shot in the back. He didn’t have any family to take him in once he was released from his lengthy sentence. Jackson sang the first performance of Don Giovanni by the Ópera na prisão programme in 2014. He wrote a Rap song he sang himself at the end of the recital, accompanied by the orchestra and waving a flag printed with the word freedom. When he was finally free, he went to the National Theatre of São Carlos in Lisbon to try to get a job. As relevant work experience, he told them he had previously sung Don Giovanni and knew the entire score by heart in Creole Italian.

It is caught in this web of creative fiction and reality that we find ourselves now. All we know for the moment is that we have to deliver finished stories to the composers by the 3rd December. Now our only hope is that no more of the guys die in real life, as we have more than enough to go on for our Traction opera.

Paulo Lameiro,with David, Sofia, Raquel, Sandra, Anabela, Carla, Nuno, Francisco, Pedro, Paulo Kellerman and many others